Joe Machnik. That name or his face just might ring a bell. You might have seen him running on the soccer field as a player, or as a referee, or on the sidelines as a coach. Or you might have participated in one of his soccer camps. Or more recently perhaps you have seen him on TV as Dr Joe, when he tackles some of the knotty problems and refereeing decisions of the beautiful game.

Call him American soccer’s renaissance man. You don’t believe that? Let’s just take a gander at his endless resume:

– He was an All-American goalkeeper at Long Island University.

– As 23-year-old head coach, he guided LIU to the 1966 NCAA championship game.

– He was a member of the 1965 US Open Cup champion New York Ukrainians, which performed in the old German-American Soccer League (now the Cosmopolitan Soccer League).

– He also played semi-pro with the Newark Ukrainian Sitch in the American Soccer League from 1967-68 (the team temporarily changed the spelling of his name to Machnyk to make it sound as though he was Ukrainian).

– He coached the men’s and women’s soccer squads at the University of New Haven, creating the program for the latter.

– He was an assistant coach with the US national team when it reached the World Cup for the first time in 40 years at Italia 90.

– He was the director of referees for three leagues – the Major Indoor Soccer League, Major League Soccer and National Premier Soccer League.

– He also coached the New York Arrows (MISL) for part of a season.

– He was commissioner of the old American Indoor Soccer Association.

– He has been a Fifa and Concacaf match commissioner.

– And most recently, that gig on Fox Sports as Dr Joe. And yes, he is a doctor – a PhD. It probably should for a doctorate in soccer, not for education. He earned that at the University of Utah when he was an assistant professor in the School of Business, Department of Sport Management at New Haven.

Heck, he even has authored two books: So You Want to be a Goalkeeper! and So Now You Are a Goalkeeper!

Is there anything he hasn’t done?

Machnik, 74, has lived the ultimate American soccer experience.

“Joe is one of the great personalities of the sport in the States, a person who has been at every level from player to coach to referee, administrator in the league with a vast experience and vast knowledge of the game in this country,” says Alfonso Mondelo, MLS’s director of player programs. “When you talk about the pioneers of the game in this country, he has to be one of them.”

Former LIU coach Arnie Ramirez, who is about the same age as Machnik, still calls him coach and phones his mentor every December to wish him a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year.

“He was very passionate about the game. He instilled that passion in us,” Ramirez says. “He always asked us for our opinion. There used to be a hot dog place we used to go for lunch and just talk about the team, the players, and how everything was going. He respected the way we played. He didn’t try to change our style of play. If you were a dribbler, he would let you dribble in a certain area in the offensive 30. He was more of a players’ coach. It wasn’t all the Xs and Os all the time. He gave us the liberty of the freedom to play.”

Growing up in the Greenpoint section of Brooklyn, Machnik was a hockey fan who regularly attended New York Rangers games at the old Madison Square Garden for only 40¢ thanks to a high school GO card. His first exposure to soccer came because of hockey. To pass the time Sundays, Machnik watched soccer matches at McCarren Park, the local public field.

As a Brooklyn Tech high school sophomore, Machnik was convinced by a classmate to become a goalkeeper.

“Brooklyn Tech had no field,” Machnik says. “We played in the gym and on the roof. The roof was screened in. I tried out and from the little that I knew about hockey – angle play and stuff, I was able to stop shots. I was crazy enough to dive on the gym floor. We put mats down. Brooklyn Tech was very good. I made the JV that year, my junior year. The varsity won the city championship. Ray Klivecka [former New York Cosmos coach] was the leading scorer in the city when they won the championship.”

They attended LIU as the first grant-in-aid athletes in the soccer program under new coach Gary Rosenthal, helping turn a team that hadn’t won a game in two years into a nationally respected side. In their first game, Klivecka scored twice and Machnik saved a penalty kick. The Blackbirds earned a berth in the 1963 NCAA tournament. “We were going to play Saturday against Bridgeport and [President] Kennedy got shot on Friday so the game was canceled.”. LIU lost the following week, 3-1.

Machnik coached LIU into the 1966 NCAA final. After marrying Barbara and having two daughters, they felt it was time to move out of the city. He wound up at New Haven coaching soccer and ice hockey.

“To tell you the truth, I could barely skate. So, I faked it,” he says. “I was smart enough to hire a really good assistant. He ran the practices pretty much and I ran the bench for three years.”

During his Sitch tenure that Machnik met Walter Chyzowych, and he two became friends until the former US national coach’s death in 1994. That friendship helped open doors for Machnik, who was assistant coach to head man John Kowalski with the US five-a-side team that won the bronze medal at the 1989 Fifa world championships (the squad boasted such future stars as Tab Ramos and Peter Vermes) and the Americans’ Italia ‘90 qualifying run.

Machnik attended the first coaching school in 1970 under the legendary Dettmar Cramer, who asked him to hold a goalkeeping session, sparking his career as a keeper coach.

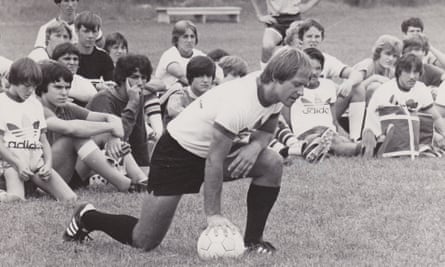

While working at some regional soccer camps, Machnik noticed that goalkeepers “were being abused” and “being used for shooting practice.” His brainstorm was to start a camp just for goalies in 1977 – the No. 1 Goalkeeper Camp. The first camp at the Taft School in Watertown, Connecticut had 39 keepers from 13 states. In the second year, at Loomis Chaffee School in Windsor, Connecticut, the camp boasted 240 goalkeepers from 39 states. The second-year staff including Danny Gaspar, the Iranian national team’s goalkeeper coach, keepers Roy Messing and Mickey Cohen and Kowalski.

“It just ballooned. By year three we were doing Chicago and LA.”

The camps have influenced generations of goalkeepers, including Jon Busch, Kevin Hartman, Nick Rimando, Matt Reis and Joe Cannon, plus former US international Hercules Gomez. Staff coaches Dave Dir (Dallas Burn) and Greg Andrulis (Columbus Crew) became MLS coaches.

Machnik eventually found himself working with Bob Gansler on the USA national team in 1989 during the Concacaf Hexagonal.

Jeff Duback started in the nets in a 1-0 opening loss, but Machnik said he convinced Gansler to go with the imposing 6ft 4in, 220lb David Vanole for the next qualifier against the Ticos in St Louis.

“The players were crazy about Vanole,” Machnik says. “He was so charismatic. He would put American flags on the side of the goal, on his arm. Against Concacaf opponents, he was a big man.”

With time running out and the US nursing a 1-0 lead, Vanole saved a penalty kick by Mauricio Montero.

“Vanole was a five-year camper of mine, so he was familiar with my theories on stopping penalties. We win the game and Vanole is the goalie.”

At least until the Marlboro Cup at Giants Stadium. Vanole entered injured and Duback was hurt in the opener against Sporting Lisbon.

“Bob has two sons graduating that day, one from high school,” Machnik says. “Bob gets permission to not be at the game and I’m the coach at the championship game and we’re going to play Peru. We have no goalkeeper. We’re in New Jersey, so let’s call Tony Meola. He’s playing for the University of Virginia. So, we bring him and he starts and he’s clearly the answer. We got four games left to qualify and he registers four shutouts.”

Machnik’s story is a reminder to never burn your bridges. MLS started. Its commissioner was Doug Logan, with whom Machnik had dealings during his AISA tenure. Machnik wrote Logan asking to help organize the referee program.

“The first year is a catastrophe because the [US Soccer] federation was not prepared to have a referee program for a pro league,” Machnik says. “They used 202 officials. The off-field structure was so chaotic that it affected the on-field performance of good referees.”

While hosting a Labor Day party, Machnik received a call from deputy commissioner Sunil Gulati, who he said the league would like to interview him to structure a referee program.

Part of the interview with MLS vice-president Bill Sage included attending a playoff game at Giants Stadium that was decided by a shootout and officiated by Esse Baharmast (who went on to referee in the 1998 World Cup and became US Soccer director of referees). The tie-breaker caused a controversy due to uncertain shootout rules as DC United coach Bruce Arena protested the loss to the NY/NJ MetroStars.

“It’s chaos. After the game, we’re walking out and we go past the two teams’ rooms and Esse comes out of the referee’s locker room and Bill Sage is standing with me, and he says, ‘Please help us’ and that’s how I got the job,” he says with a laugh.

Machnik must have done something right. He stayed with the league for 15 years.

“Certainly, every year was an improvement. We did get to get four [referees] to become full-time back then, but that wasn’t enough. Full-time had to be the way to go because fitness is such an important part of refereeing. You’ve got to have the right angle on the play. The only way to have the right angle is to be fit. We had all kinds of painters, school teachers, insurance agents, truck drivers. A lot of guys struggled to be fit.”

With the advent of the Professional Referees Organization in 2012, Machnik saw the writing on the wall and resigned. “There’s no hard feelings one way or another,” he says.

As one door closes, another one opens. In this case, two. One was a short stint as NPSL director of officials in 2014, the other an opportunity to become a TV personality. Machnik aced the screen test with Fox and got his gig as soccer rules analyst.

He has worked the Gold Cup, Women’s World Cup and MLS matches, sometimes from the studio, sometimes from home.

“The time is very limited and you can’t break into the middle of a game,” he says. “So, you’re doing it at half-time or in the postgame. So, I now have a TV studio in my house.”

Machnik has communicated to announcers to look at a particular player or has commented on the quality of officiating. “Actually, the announcers sometimes use some of my stuff,” he says. “If they have time, in LA they have a switch, the lights come on, the camera comes on – I watch the games in a shirt and tie. I have a jacket ready to go and if something happens I speak about it.”

Not only has he seen it all, Machnik has appreciated the growth of a sport that struggled to earn recognition the past five decades.

“My first television game of any significance was the Tottenham-Leicester City FA Cup final on the Wide World of Sports in 1961. I was working part-time in the supermarket, A&P. The guy knew I was playing for LIU and he let me off and come back after the game, just to go home and see the game.”

In the CSL, Machnik played on fields whose quality level was questionable.

“I often think about Walter, if he was alive today, he would have been amazed,” Machnik says. “The facilities, the complexes. We struggled to find a field. Eintracht Oval, Metropolitan Oval. We played in a parking lot on Grand Avenue. It’s called Grand Stadium.”

Machnik noted that during its 1990 qualifying run, the US played at St Louis Soccer Park in front of as few as 3,700 spectators (for the scoreless draw with El Salvador on 5 November 1989].

Today, soccer is 24/7 on TV and just about every MLS team has a stadium it can call its own.

Machnik has few regrets. “I wish I was a better player,” he says. “I wish I refereed in the NASL, which I didn’t. But I made a decision to go indoor. That pretty much ended my chance of making it in the NASL.

“I’ve been through a couple of failures, MISL, AISA. After [commissioner Don] Garber first came to MLS, we contracted. We took salary cuts in the office. I would sometimes think he would probably [have] thought that ‘why did he do this? This is going to be a career-ending decision.’ We went from 12 to 10 [teams]. We had four owners for the rest of the teams. Those guys kept it alive. I don’t think there’s any chance that it’s not here to stay.”

Trying to choose his No 1 moment was not an easy task.

Coaching at Italia 90 certainly was up there. “It was significant for me, but for my family. Everybody came, all the kids came.”

So was officiating the 1981 MISL all-star game at Madison Square Garden. It was a big deal for Machnik, who rooted for the hockey Rangers from the stands.

He believes he is the only man to have coached in the two finals – Division I in 1966 and Division II with New Haven in 1976 and officiated an NCAA D1 final – Indiana v Howard University in 1988.

During the 1983-84 MISL season Machnik went from working the middle as a referee to working behind the Arrows’ bench. “We had a couple of injuries and I could have signed myself as a player, kicked out the first ball and done referee, coach, player all in one year,” he says. “But I didn’t. I respected the game too much.”

The game has returned that respect. Machnik is a member of five halls of fame. That includes LIU and New Haven, the Connecticut and New England Soccer halls and the National Intercollegiate Soccer Officials of America Hall.

Actually, there is one missing line on his resume – the National Soccer Hall of Fame. Given his lifetime of devotion to the game, perhaps that will change for American soccer’s renaissance man.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion