The two histories of Turtle Crossing

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

We need your support!

Local journalism needs your support!

As we navigate through unprecedented times, our journalists are working harder than ever to bring you the latest local updates to keep you safe and informed.

Now, more than ever, we need your support.

Starting at $14.99 plus taxes every four weeks you can access your Brandon Sun online and full access to all content as it appears on our website.

Subscribe Nowor call circulation directly at (204) 727-0527.

Your pledge helps to ensure we provide the news that matters most to your community!

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 04/06/2021 (1056 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

A section of land, with two separate but connected histories, lies along the Assiniboine River west of 18th Street in Brandon.

The first is not a happy history. From 1895 to 1971, those that ran the Brandon Residential School took Indigenous children from their home communities in an attempt to assimilate them into colonial society established by European settlers.

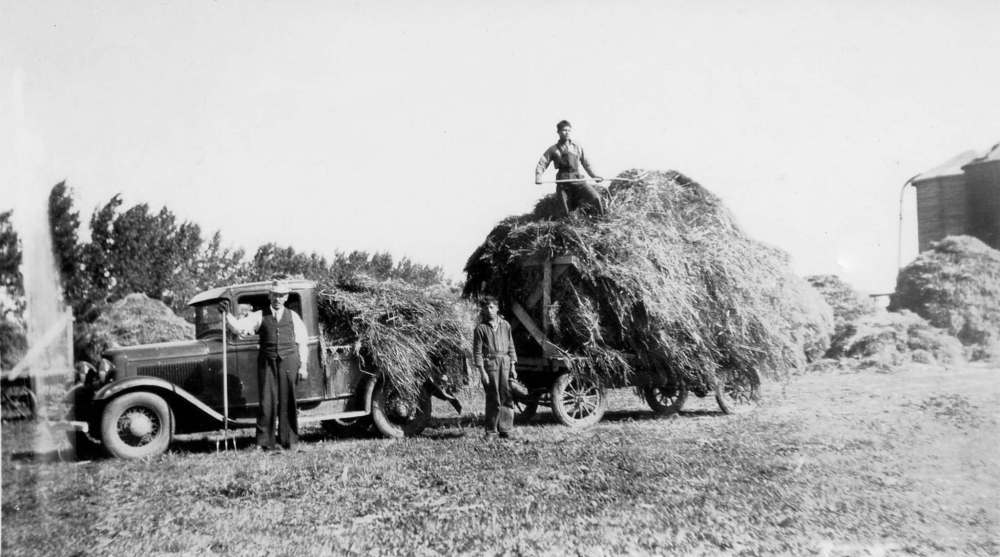

Students lived in poor conditions, were made to perform manual labour on the school’s farm and frequently got sick and died from diseases such as tuberculosis.

Sioux Valley Dakota Nation, the nearest First Nation to the school, has done research indicating the presence of more than 100 potential unmarked graves, that span over three locations, of students who died while attending the school — one on land owned by the nation, one at a nearby experimental farm, and one at a nearby private campground.

The second history is a bumpy one, but not nearly as brutal.

In the 1920s, the City of Brandon leased land around the school to turn into a park that was eventually named after the alderman who pushed for its development.

Though children at the school suffered, locals used the park for decades as a spot for sports and swimming. The residents of Brandon used it as a spot for celebrations such as Manitoba’s centennial in 1970 and camping.

The park has seen its fair share of troubles, especially relating to lengthy delays in developing the site for public use and damage caused every time the nearby river spilled over its banks and flooded the site.

Despite the connection between the school and the nearby park, what happened at the school was rarely mentioned when talking about the park.

The discovery of 215 children buried in unmarked graves on the grounds of the former Kamloops Residential School in British Columbia that was announced last week came as a shock to many, but it has been public knowledge that children were buried near Brandon’s school since at least the 1970s when a memorial was erected by local Girl Guides commemorating them.

The issue of campers using a campground where dead Indigenous children are buried came up in 2015 and 2018, when Sioux Valley expressed an interest in repatriating the bodies, but an agreement with the current owners of the campground has yet to be worked out.

In 2019, a Brandon University team receivied funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada to begin a search, but the pandemic has interrupted that work.

After the Kamloops discovery was announced last week, Brandon’s former residential school has been brought back into the spotlight.

On Friday, Brandon University announced it is partnering with Sioux Valley, Simon Fraser University and the University of Windsor to find and identify the buried children. A spokesperson for the university told the Sun that the project funding does not include resources for searching the campground.

To explain how the story started and reached the point it’s at today, the following is a brief recollection of the two histories of what is currently called Turtle Crossing.

In 1891, preparatory work began for the building of what was then referred to as the “Indian Industrial School.”

A June 17 article from the Winnipeg Tribune on a recent Methodist Church conference noted Brandon had been selected as the location for a residential school run by the church. Carberry had also been in the running.

The Methodist Church would later merge with three other Protestant churches to form the United Church of Canada in 1925.

The Sept. 24 edition of the Sun from that same year ran a front-page article saying an engineer from the government had arrived in Brandon to take levels and topographical notes for the benefit of the architect of the school.

In the May 14, 1895, issue of the Winnipeg Free Press, it was reported Rev. John Semmens had received a commission as the superintendent for the residential school in Brandon.

An article in the Winnipeg Tribune from June 6, 1895, stated Semmens was on his way to Norway House and other communities on Lake Winnipeg to collect 40 to 50 students for the school, a mark he fell short of.

When heading northward, Semmens recorded several questions frequently asked by parents, including if the children would return after their studies were completed, was it the government’s plan to destroy their languages and tribal life, whether their children would be enslaved and exploited for money, if the children could freely return home by their own decision or the decision of their parents and if the government would actually keep their promises surrounding the schools.

The Brandon Residential School first opened in July 1895 with room for 125 students, though only 35 children were enrolled at first, according to an article on The United Church of Canada’s website.

“When Semmens expressed his concern about the resistance he had encountered, the Department of Indian Affairs promised to enforce, if necessary, federal regulations stipulating the “compulsory education of Indian children,” the United Church’s article notes.

First Nations communities were not consulted about the location of the school, which led Berens River Chief Jacob Berens to petition the government and church for a closer school.

“Our hearts are sad for we cannot think of sending our children away, such a long distance from their people and their homes … we love our children like the white man and are pleased to have them near us,” Berens wrote to the church’s mission board.

The distance between farther-away First Nations and the school was one of the contributors to low enrolment, with many hesitant to send their children so far away.

A deadly period for the school existed between 1898 and 1906, according to the church. More than 25 children died, while others were sent home after becoming seriously ill. The main cause of death in the early days was tuberculosis.

A 1903 recruitment trip ended in disaster when a reverend from the school, six children and an adult Indigenous man all drowned while sailing on Lake Manitoba.

Despite the deaths at the school, the church states administrators did not attribute those deaths to the conditions at the facility, typically reporting that the school environment was healthy.

One inspector from 1918 did provide a more honest report, noting students were sick with tuberculosis, open wounds, concussions, food poisoning, flu and measles.

“The Nurse reports (though she refuses to put it in writing), that since February 1917, there were three deaths from tuberculosis,” reads a quote from the inspector’s report.

On June 25, 1912, the Sun ran an article stating that Rev. Thompson Ferrier, the contemporary principal of the school, voiced his approval of transferring some of the land surrounding the school to the city, on the condition that authorities in Ottawa were in favour as well.

An article from the next day’s edition of the Sun mentions the land on which the residential school resided was purchased by the city and “presented” to the government of the then-Dominion of Canada so the school could be built on it.

Page 3 of the Oct. 9, 1919, edition of the Sun reported city council was directing the parks board to lease 56 acres of land from the residential school site for 99 years for the cost of $6,000.

“A lease of the property for ninety-nine years was all that could be handled at present, as the land could not be bought outright,” the story reads.

That lease combined with a further 56 acres of land being provided by an unspecified higher level of government would result in the creation of a 112-acre park along the Assiniboine River.

The City of Brandon’s records and information manager Ian Richards provided the Sun with some information from surviving documents regarding the city’s dealings with the land.

Unfortunately, there isn’t a lot of information. Richards hypothesizes this could be for a few reasons.

The first is that the city was not directly involved with the operation of the school.

Secondly, in the early 2000s, the city decentralized responsibility for record-keeping, going from a central registry to requiring departments to be responsible for their own documents. This meant that records were not kept consistently and some records may have been lost or destroyed.

Finally, the city’s recreation department, the final city department responsible for the park, was disbanded in the early 2000s. There were no policies on what to do with records from disbanded departments and some materials that would be archived in the present day may have been destroyed.

Richards was able to find was the list of conditions for the lease agreement between the school and the city.

Apart from the 99-year duration of the agreement, the city was also required to use the land exclusively as a park or else it would revert to the school.

During the summers, police were required to patrol the park “with specific instructions for the protection of our Indian girls.”

The school also retained the right to have students swim in and skate on Lake Percy and for horses and cattle to be allowed to water at the lake. Allowances were also given to let the school manage land under crop for the next three years.

A streetcar line was supposed to be built to the land’s eastern entrance, though this never got off the ground.

“By 1918 the street railway was in financial trouble and I’m not certain how much thought would have been given to extending it as required by the lease,” Richards wrote in an email.

It was a long time before work actually began on turning the land into a park.

The next year, the April 27, 1920 edition of the Sun stated Ferrier had made trips to both Ottawa and Toronto to secure permission for leasing the land to the city. A cheque had been issued to the Department of Indian Affairs in January of that year, but the city was still waiting to receive the lease.

It was reported on May 26, 1920, that work would begin on clearing the land to create the park by June.

The park still wasn’t ready five years later. The May 28, 1925, edition of the Sun reported that floods during the previous two years had thwarted plans to improve the land and that road work would begin that year.

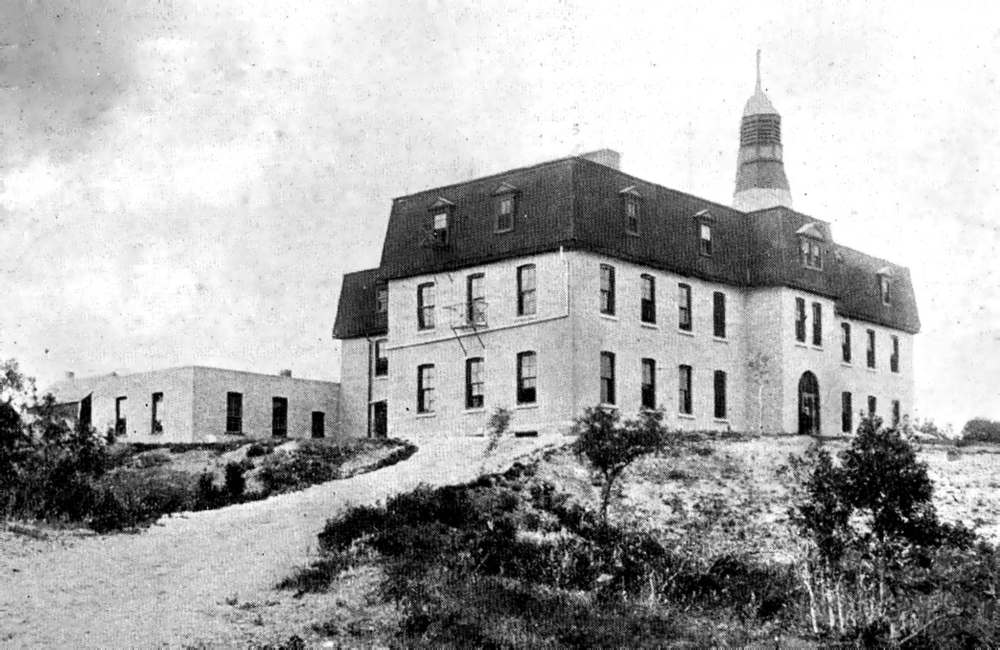

By 1928, the original residential school building had become run down and needed replacing. The May 12 edition of the Sun reported the replacement was estimated to cost more than $100,000 and construction was expected to take until 1929 to complete.

Both buildings were located on the same spot on a hill overlooking the park.

According to the United Church, the new building didn’t open until 1930, but the original building was demolished in 1929. During construction, students were temporarily sent back to their home communities. Eighty-three orphans were sent to a residential school in Edmonton.

In 1931, after the beginning of the great depression, a member of city council proposed hiring unemployed locals to work on the park as a relief program.

The park finally seems to have gotten some use though, with the Knights of Columbus holding a summer picnic there that same month. That picnic included a softball tournament, with one team captained by a young Turk Broda, who would later win five Stanley Cups, two Vezina Trophies and be inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame as a Toronto Maple Leaf.

From that point on, it became a popular fishing and swimming spot, though there were semi-regular drowning deaths among those swimming in the river.

There were few stories about Indigenous children who died at the school in the pages of the Sun, but the death of a 15-year old named Mary Sutherland from the Lake of the Woods area in Ontario was noted in the Dec. 6, 1932 edition. Sutherland died from complications from a mastoid operation, a procedure used to deal with persistent or untreated middle-ear infections.

Though he had graduated from the school year previously and died in a hospital in the Selkirk area, the Sun reported on August 20, 1942, that 28-year old Ewart Monias had his funeral at the residential school’s chapel and was buried in its cemetery.

The United Church states that in 1942 alone, at least 12 children aged 10 to 15 ran away from the residential school. The church’s superintendent of missions blamed the Second World War for constraining access to staff and supplies, leading to the runaways.

Parents sent petitions about the low-quality food their children were being fed and one Brandonite gave a report to the RCMP about rumours of abusive treatment by school staff.

Children running away became such as issue at the school that the Department of Indian Affairs launched a formal investigation into the matter in 1951.

Manitoba’s residential schools received a feature treatment in the Jan. 10, 1959 issue of the Winnipeg Free Press in an article with the racist headline “Indians learn white man’s way.”

The system’s goal of destroying Indigenous cultures was on full display in the following excerpt from this article, about one of the teachers at the Brandon Residential School:

“After their term at the school is over in June, they return to their reservation homes for the summer holidays. Looking at conditions on the reserve through eyes trained at the Brandon Residential School, it is Mr. McLean’s fond hope that his young students will become discontented there and finally decide to leave the reservation to take their places in society.”

By 1963, the city had renamed the park from the generic “Suburban Park” to “Curran Park,” named after an alderman pivotal in its creation.

The city was also trying to offload the property. Then-Mayor S.A. Magnacca and Ald. William Boreskie clashed at a special council meeting on May 24, 1963, over the fate of the park.

The parks committee had recommended the YMCA take over operations at the park, in part because of its excellent record of running the Kiwanis Pool. Magnacca told council that the YMCA had no interest in taking over the park, especially as it was in the middle of a fundraising campaign. The organization would only run the park if the city could not find anyone else to do so.

Boreskie then asked why the mayor and the city manager hadn’t brought this up before, hinting that they’d known that was the case for some time. The mayor objected to his colleague’s words, sparking an argument that only ceased when Magnacca threatened to have Boreskie charged under the Municipal Act for his conduct.

A 1970 article about the park stated the Girl Guides of Canada were in the midst of restoring the children’s cemetery at the old residential school. A new fence had been erected around it and flowers were planted in the centre.

Two years later, the Girl Guides unveiled a plaque that would be attached to a stone cairn dedicated to those buried in the cemetery. The stone has since been moved and the plaque has disappeared.

“The Brandon Student Residence, formerly called the Indian Residential School, will close June 30 and its assets sold if no further government use can be made of it,” a Sun article from March 29, 1972, reported.

Former provincial Industry and Commerce Minister Len Evans was reported to have sent a telegram to then-federal Indian Affairs Minister and future Prime Minister Jean Chrétien protesting the closure of the facility and the loss of jobs it would cause.

Evans’s pleas did not save the building, which closed as scheduled.

Though the Sun reported in August 1973 that there had been interest in the building, a sale had yet to materialize. Possible plans to convert the building into a youth hostel or have the experimental farm take it over both fell through.

In January 1982, the Sun reported that then-Sioux Valley Chief Bob Wasicuna proposed the abandoned residential school be replaced with housing units for Indigenous students. Though other groups, including the RM of Cornwallis, were also interested in the school, Wasicuna argued that Indigenous people should be given first access.

By March, Wasicuna had been replaced by Allan Pratt as chief, who said he was willing to work with the RM of Cornwallis on an alternative to tearing down the building.

Though a representative from the Department of Indian Affairs told the Sun in January 1985 that the old school building was too old and deteriorated to be used anymore, it didn’t stop the department from refusing an offer on the building from Sioux Valley.

By that time, the RM of Cornwallis had lost interest in the building and property.

In 1990, a former student at the school named Bill Thomas gave an interview to the Sun saying that physical and emotional abuse was common at the local residential school. He also said he’d heard stories of even more serious physical and sexual abuse at the school.

He detailed instances of witnessing racist insults directed at children as well as brutal physical punishments during his time at the school between 1943 and 1951.

The old residential school building was finally demolished in 2000.

According to Richards, the property was surveyed by the city when the lease went through. However, he doubts that old surveys would be helpful in locating cemeteries or burial sites, given that the site frequently flooded over the decades and landscaping had changed the land significantly.

The minutes from a Brandon City Council meeting from Oct. 30, 2000, provided by Richards, helps explain why the city decided to sell the park.

Constant flooding made for high maintenance costs and losses of revenue from campsites becoming unusable. The park incurred an $89,000 deficit in 2002 alone.

If the city was unable to find a buyer, it was suggested that the whole land or portions of it could be leased. One city employee stressed that if this were to occur, the burial ground would need to be maintained or subdivided out.

The Sun article from the subsequent day reported that “as a condition of any lease or sale agreement, the operator must leave intact an Aboriginal burial ground that dates back to the 1920s.”

Curran Park was finally sold by the city for $130,000 in February 2001 to Gerald Voth.

After just a single season operating the park, Voth put the park up for sale in January 2002. Spring flooding delayed the opening of his park and the province ordered him to close the on-site pool.

In May of the same year, Maxine Cyr purchased the park. She owned it until 2007, when current owners Mark and Joan Kovatch bought it and renamed it Turtle Crossing.

In 2007, the First Nation was considering the former school property as a potential casino site, which never came to pass.

In an editorial by Deveryn Ross in the Winnipeg Free Press on Dec. 18, 2015, it was pointed out that the final report by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission referenced a 1935 report stating four out of five children entering the residential school in Brandon had evidence of tuberculosis.

Ross noted that the previous year, a forensic report published by Katherine Nichols found records hinting that at least 70 students had died while attending the school. She was certain that number did not represent all the students who died at the school.

Nichols also found that the cemetery with a marker listing only 11 names actually contained the remains of up to 26 people. She was not allowed access to the Curran Park/Turtle Crossing site.

Another proposed development for the site came in 2016 when Sioux Valley proposed a 30-bed healing lodge for the former school site. It also would not come to pass.

In June 2018, then-Sioux Valley chief Vince Tacan declared an interest in Sioux Valley repatriating bodies from the campground site. At the time, Kovatch said he had seen “adequate evidence” that residential school survivors were buried on his property, but was unsure of their exact location.

“Although Sioux Valley Dakota Nation is heading the effort to repatriate whatever graves might exist at the Turtle Crossing property, Tacan said that it’s only because they are the closest First Nation to the site,” the Sun reported.

Both the City of Brandon and the Kovatches were said to be open to working together on the issue.

At present, the repatriation of bodies has not yet occurred. The discovery of the bodies of children in unmarked graves at the Kamloops Residential School has sparked interest in further searches at the other residential schools in Canada.

Sioux Valley issued a statement on June 1 of this year about the current status of the project.

“With funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Partnership Development Grant, we are collaborating with university partners to conduct this investigation,” the statement reads. “While employing archaeological survey techniques, geophysical technologies, survivor accounts, and archival documents, our investigation has identified 104 potential graves in all three cemeteries, and that only 78 are accountable through cemetery burial records.”

The First Nation also called for the federal government to implement the Truth and Reconciliation’s Calls to Action and put more work into identifying and protecting residential school cemeteries.

“We must honour the memory of the children who never made it home by holding the Government of Canada, Churches, and all responsible parties accountable for their inhumane actions,” the statement concludes.

“There is more work to be done to bring truth to the atrocities afflicted on the children, who were our parents, our grandparents, and great-grandparents, and those children who never became parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents.

“The families and communities whose children were lost while attending these schools have questions that deserve answers. The children buried at these sites must have their identities restored and their stories told. They will never be forgotten.”

» cslark@brandonsun.com

» Twitter: @ColinSlark